Over the past seven weeks, I’ve presented nearly 50 timetables from the Rumsey map collection ranging from 1872 to 1907. Among other things, these timetables showed the evolution of train names, from no names to type names such as “accommodation” and “express,” to destination-oriented names such as “Chicago Express” and “Pacific Express,” and finally to evocative names such as Golden Gate Special and Sunset Limited.

Click image to download a 7.8-MB PDF of this booklet.

Click image to download a 7.8-MB PDF of this booklet.

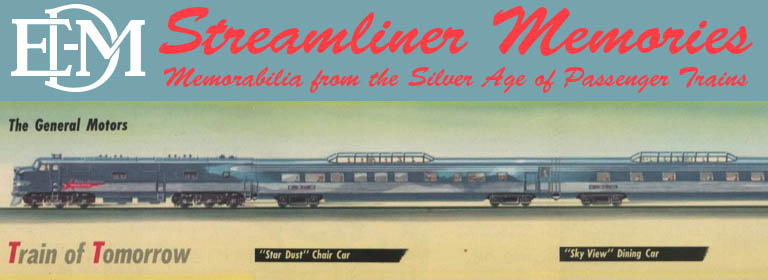

The use of these evocative names greatly increased in the 20th century, when a major revolution in passenger railroading took place. Streamliner Memories has previously looked at the new technologies that allowed the streamliner revolution in the 1930s: air conditioning, Diesel locomotion, and lighter weight metals such as aluminum, Corten steel, and stainless steel.

Today I’m going to start looking at the changes that allowed for a previous revolution that took place from about 1905 to 1915. We might call this the heavyweight revolution, but that term only came into use with the introduction of lightweight streamlined cars in the 1930s. In the 1905-1915 era, it would have been called the all-steel revolution as it saw the replacement, on first-class trains at least, of wooden passenger cars with all-steel cars.

Several things were vital for this revolution to take place: First was the consolidation of the railroad industry and the competition that generated, which is the subject of today’s post. Second was the development of all-steel cars, which I’ll describe tomorrow. Third were more powerful locomotives to pull those cars, which I’ll discuss the day after tomorrow. Finally, the railroads had to replace the 90- to 100-pound-per-yard rail typical of 1900 with 120- to 132-pound rail and beef up some bridges, factors that I won’t go into in detail.

The 1960 Association of American Railroads booklet shown above (and the 1950 edition presented yesterday) contains a series of maps of the nation’s rail system in various years from 1830 to 1950/1960 (depending on the edition). As of 1850, the U.S. had more than 9,000 miles of railroads, but they consisted of a lot of short lines that weren’t connected with one another. Another 21,600 miles had been built by 1860 and almost all of the lines met together. However, there were many changes of gauge and even more changes of ownership, so there were few through trains over long distances.

By 1886, the narrow-gauge railroads of the South and broad-gauge railroads of the North, such as the Erie, had almost all converted to standard gauge. This allowed interchange, but through trains were still the exception rather than the rule.

The 1880s also saw the largest growth of the nation’s railroad system: more than 70,000 miles were built in that decade, a 75-percent increase of the system as a whole. By 1900, the nation had 193,000 route-miles of rail lines, and the St. Paul’s Pacific extension, the Los Angeles & Salt Lake, Southern Pacific’s Coast Line between San Francisco and Los Angeles, and the Spokane, Portland & Seattle lines to Portland and Bend were all yet to be built.

For some reason, the AAR booklets didn’t include a map showing railroads in 1916, when the nation’s network reached its maximum route-miles. This map, while not as clear as the AAR maps, represents 1916.

For some reason, the AAR booklets didn’t include a map showing railroads in 1916, when the nation’s network reached its maximum route-miles. This map, while not as clear as the AAR maps, represents 1916.

The nation’s railway system reached its maximum extent of about 254,000 route-miles in 1916. A few lines were still unbuilt, including the Southern Pacific’s Natron Cutoff, Great Northern’s line to California, and Burlington’s line through Wyoming’s Wind River Canyon, but pretty much the system was fully fleshed out.

Click image to download a 4.7-PDF of this 1918 bachelor’s thesis.

Click image to download a 4.7-PDF of this 1918 bachelor’s thesis.

A 1918 bachelor’s thesis by a University of Illinois student named William Klink on the effects of this growth on passenger train schedules has been immortalized at archive.org. Klink noted that the rapid growth of the 1880s was followed by a period of consolidation of the railroad industry. This consolidation generally consisted of the acquisition or merger of end-to-end routes, such as New York-Buffalo railroads buying Buffalo-Chicago railroads.

These consolidations allowed for more through trains. But they also created competition for passengers as there were multiple railroads serving major corridors. Some of the most important corridors, several of which are discussed in detail in Klink’s thesis, were New York-Chicago, New York-Florida, Chicago-Twin Cities, Chicago-St. Louis, Chicago-Denver, Chicago-Los Angeles, Chicago-Portland/Seattle, and Chicago-San Francisco.

Most of these corridors saw intense competition between two, three, and sometimes more railroads or routes. At least seven railroads served the Chicago-Twin Cities corridor. Such competition, in turn, generated increased speeds and service quality. By 1910, the average speed of the fastest trains in some corridors were almost twice the average speeds of trains in those corridors in 1880. Competition also led to a dramatic increase in the quality of service.

In short, consolidation and competition led to the widespread use of the limited train concept that first appeared in 1881. Initially, at least, limiteds carried only parlor cars and sleeping cars, but no plebian coaches.

Unlike the previous express trains, which didn’t stop everywhere but still made lots of stops, many limited trains made very few stops, sometimes stopping only to change crews and/or service the locomotives. The original 20th Century Limited, for example, only carried passengers between New York and Chicago and did not board or deboard passengers at any of the service stops between.

To underscore the first-class nature of their trains, some railroads charged extra fares to ride their limiteds, meaning a surcharge above the ordinary first-class fare. This extra fare was advertised as a feature, as it helped ensure that passengers on the train would share their spaces only with other people in their income group.

In 1910, Klink says, the New York Central had 18 extra-fare trains and the Pennsylvania had 13. The Central’s increased to 30 by 1917, though Klink doesn’t say how many the Pennsylvania had in that year. Other extra-fare trains included the Santa Fe de Luxe, C&NW/UP/SP Overland Limited, and Southern Pacific Shasta Limited. For some reason, the Sunset Limited and North Coast Limited never charged extra fares even though at various times both were all-Pullman trains with limited numbers of stops.

A 1929 survey of extra-fare trains by Time magazine found that the New York Central charged an extra fare for four New York-Chicago trains and one New York-St. Louis train. The Pennsylvania charged for three New York-Chicago trains, one New York-St. Louis train, and one New York-Washington train. Other extra-fare trains included the Crescent, Panama Limited, Chief (which was down to 58 hours), Overland Limited (ditto), and Portland-San Francisco Cascade Limited. Neither the Chicago-Pacific Northwest nor the Florida railroads charge extra fares. These extra fares earned railroads $10 million a year (well over $150 million today), revenue justified to the Interstate Commerce Commission by the trains’ extra speed and service.

Extra fares or not, the growth, consolidation, and competition of America’s rail network generated its own demand. It allowed the development of areas that were once considered remote. This led to a huge increase in trade between regions. That generated more passenger traffic between those regions.

Before 1880, few people other than actual settlers traveled to the Far West and most businesses were local. By 1910, most travel to and from California and other western states was tourists and businessmen managing their increasingly nationwide companies. This increase in demand also led to the need for longer, safer trains, which is what generated the all-steel revolution.