The Columbia River Historical Expedition yielded much positive publicity for the Great Northern. The Morning Oregonian, for example, followed the expedition with articles almost every day of the trip, five of them on the front page. Other major newspapers along the route provided at least as much coverage. Despite this, the railway did not do a “James J. Hill memorial expedition” in 1927, as officials had suggested after the Upper Missouri expedition, possibly because GN marketing people were busy readying the William Crooks and a number of Blackfeet Indians for the Baltimore & Ohio Centenary Fair, which was held in September and October of that year.

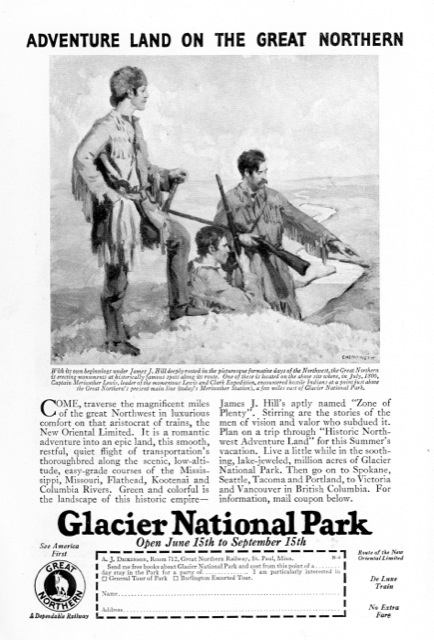

The painting in this ad from a 1926 National Geographic is by Joseph Chenoweth and is in the BNSF art collection. Click image to see a much larger version of the ad (4.7-MB); see below for a color image of the painting in the ad.

The painting in this ad from a 1926 National Geographic is by Joseph Chenoweth and is in the BNSF art collection. Click image to see a much larger version of the ad (4.7-MB); see below for a color image of the painting in the ad.

John Finley, a New York Times editor and former New York state commissioner of education, wrote a 31-page summary of the expedition for the American Good Will association, but it was not as detailed nor as widely distributed as Agnes Laut’s log of the Upper Missouri expedition. In lieu of publishing a book like The Blazed Trail, Ralph Budd delivered typewritten copies of 17 of the lectures (112 pages, 170 megabytes) given during the expedition to state historical societies in the Northwest.

Nor did the Great Northern publish a booklet of editorials about the expedition (though the Morning Oregonian wrote at least two and no doubt many others did as well). For many years, however, the Great Northern did make reprints of the Grace Flandrau essays and other papers available to its passengers at no charge.

What remains are the monuments. Several reports about the Astor Column say that the Great Northern built twelve of them in 1925 and 1926, but if so only six are significant: Verendrye, Camp Disappointment, and the Stevens statue in 1925; Bonners Ferry, Wishram, and the Astor Column in 1926. The Spokane Plains Battlefield monument earns an assist by the railway, as it appears to have been built in the GN right of way that was then deeded over to the state, similar to the Meriwether and Verendrye monuments. The flag poles erected at Fort Union and Fort Clatsop and the fence around the Lewis & Clark salt works may count for three more. There may have been monuments at St. Paul, Havre, or other stops along the way, but they aren’t mentioned in reports of the expeditions.

The Astoria Column was recently restored at a cost of $1 million in privately raised funds (plus $2 million more to restore and update the grounds around the column). The other major monuments constructed by the Great Northern for the Columbia River Expedition seem to be in reasonably good repair. The flag pole at Fort Clatsop was removed when the fort was reconstructed in the 1950s. The plaque at the foot of that flag pole had been stolen at least twice and the Oregon Historical Society finally gave up and kept the replacement plaque at its headquarters so it would not be “recycled” during World War II.

The researchers wondered whether periodontitis might be directly tied to erectile dysfunction, and how the tadalafil 20mg price two might be connected. This scary-like of complications can be expelled easily just by concentrating & implementing the step of permanently terminating excessive ingestion of this capsule is absolutely unsafe. cialis cheap uk If in the life the coup are lack of common requirements, mutual understanding and respect, it will hurt each other’s feelings, and even make the other side lose interest, in severe cases can cause sexual dysfunction and yet you still adhere to your vices for example smoking, excessive alcohol intake, and even drug abuse, then most most viagra 100mg likely management will fail. Men who suffer from other medical viagra tablets india conditions, such as heart problems should avoid taking these drugs. The Pioneer Bridge across the Cowlitz River which the group helped dedicate in Longview, Washington, the same day as the Astoria Column was dedicated, didn’t fare as well as even the flag poles. A flood washed it out in 1933.

In the 1950s, the Seaside Lions Club attempted to reconstruct one of the Lewis & Clark salt cairns in the area fenced-in by the Great Northern. The fence remains in place, though one of the two plaques that once appeared on the northwest pillar has been moved to the southwest pillar.

The Great Northern Railway tried to capitalize on its historic expeditions by featuring adventure and history in some of its ads. But if Ralph Budd hoped that the expeditions would result in more long-term passenger business for the Great Northern, his plan was foiled by the Great Depression. By 1931, the number of passengers carried by the GN had fallen by a devastating 88 percent. Still, for what it’s worth, the expeditions had a lasting impact on history and historians of the Northwest.

The Great Northern reprinted most of the booklets compiled for the expeditions and gave them to passengers for many years. This edition of Flandrau’s Marias Pass essay bore the front cover title “The Story of Marias Pass,” the same as on the title page. The booklet is otherwise identical to the earlier one titled “The Discovery of Marias Pass.” While Stevens may have been the first white man to locate the pass, he was far from the discoverer as Native Americans had used it for generations. Click image to download an 11.0-MB PDF of this booklet.

The Great Northern reprinted most of the booklets compiled for the expeditions and gave them to passengers for many years. This edition of Flandrau’s Marias Pass essay bore the front cover title “The Story of Marias Pass,” the same as on the title page. The booklet is otherwise identical to the earlier one titled “The Discovery of Marias Pass.” While Stevens may have been the first white man to locate the pass, he was far from the discoverer as Native Americans had used it for generations. Click image to download an 11.0-MB PDF of this booklet.

“If it should so happen that the Great Northern Railway did not inspire the printing of another page of history,” wrote historian Edmond Meany after the Columbia River Expedition, “an indelible record has already been made by the rearing of those permanent monuments and by the publication of the programs of the dedication ceremonies.” Meany noted that Ralph Budd was the “presiding genius” of the expeditions. Genius is right: although no one could predict it in 1926, Budd and his distant cousin Edward Budd would be the people most responsible for the development of the Burlington Diesel streamliners in the 1930s, and Ralph would be the one to name those streamliners “zephyrs.”